Written By: Maitrey Singh, O. P. Jindal Global University

Introduction

The easy access to music that we have today is a product of technological developments that happened over time. While today we have online streaming services, earlier we had Music CDs and vinyl records. Mechanical reproduction of music was introduced with mechanical music boxes but due to their negligible market presence they did not concern the attention of the music producers. Following the musical boxes, piano rolls were introduced.

These piano rolls were made up of paper with holes on them, when put into a player piano, these rolls would spin while air would pass through the holes. This whole process would ultimately reproduce the musical composition mechanically. These piano rolls had a substantial market presence and the music composers objected to their work being reproduced without their consent. The idea of mechanical right licenses was introduced first in the US with the The US Copyright Act, 1909 which recognized piano rolls as mechanical reproduction of a copyright work.

What are Mechanical Rights Licenses

The IPRS website defines a ‘mechanical right’ as a right to reproduce and store a work including in an electronic form. This right is enshrined under Section 14 (a)(i) of the Copyright Act, 1947 (The Act, 1947). The provision gives the author of the work the right to reproduce and store the work. Section 14 (e) of The Act, 1947 deals specifically with the reproduction and storage of sound recordings.

A mechanical rights license is required when a person other than the author reproduces the sound recording or stores it, as these are the exclusive rights of the author under Section 14 of the Act, 1947. A licensee’s rights here are restricted to reproduce the work in an audio-only format. The most popular use of mechanical rights is for making cover versions of the sound recordings, but mechanical rights are also required when the work must be distributed, either in physical form as CDs or in a Digital Format such as on online music streaming platforms.

Obtaining Mechanical Rights License

A mechanical right may be obtained from the author of the work as per Section 30 of The Act, 1947. In a situation where a broadcasting company wants to share musical work with the public on its platform, given that the work is already published, a statutory license under Section 31D of The Act would be required. For obtaining a statutory license does not require the permission of the author or their agents, instead, the same is granted on fulfillment of the requirements given under statute.

In a nutshell, Section 31D, The Act, 1947 requires the broadcasting agency to give notice to the author, displaying their intent of broadcasting the music. The notice should include the duration and the territoriality of the broadcast.[1] The broadcasting company would also be liable to pay a royalty to the author as decided by the Appellate Board. For making and uploading a cover version of the song, Section 31C of The Act would be applied which has similar requirements as 31D and requires the consent of the author of the work.

Case laws

Bombay High Court in IPRS v Harsh Vardhan Samor has highlighted the fact that mechanical rights can either be given by the author of the work or if the author is a member of a registered copyright society such as the IPRS then the society may also grant the mechanical rights license. Furthermore, in the case of Gramophone Company Of India Ltd. v. Super Cassette Industries Ltd. it was held that under Section 31C of The Act, 1947 consent of the author of the work would not be required if the work has been made public in the past and has allowed mechanical reproduction of the work. Only a notice to the author or the IPRS is required, and the relevant royalties are to be paid.

Mechanical Rights Licenses in the United States

As the United States was the first jurisdiction to recognize such licenses, thereby, it is imperative to see how licensing functions there today. In the US, Section 115 of the Copyright Act, 1976 enshrines the idea of Mechanical Right Licenses. The said section makes it mandatory for a person to take license from the author of the musical composition before reproducing the ‘phonorecords’. The Congress had added multiple conditions on licensing of mechanical rights when such rights gained popularity. These conditions include, mechanical rights can only be licensed after the work has been made public through the consent of the copyright holder.

Furthermore, the license can only be granted to an individual whose sole objective is to reproduce the music. A notice of intention must be served compulsorily to the copyright holders before reproducing the musical work. In 2018, the Musical Work Modernization Act was passed.[2] The essence of this legislation is to streamline the process of copyright licensing in musical work, making it easier for the copyright holder as well as the licensee to obtain Mechanical Rights License.

The legislation aims to achieve this goal by making a blanket platform for distribution of licenses through the introduction of body known as the “Mechanical Licensing Collective”. This body would receive the notices and royalties on the behalf of the music producers. The body is also entrusted with the duty of identifying the true owner of the copyright and making sure that they receive their fair share of royalties.

Royalties In India

When an author gives a Mechanical license to a broadcaster for their work, under Section 31D of The Act, 1947 the author must be paid royalty as decided by the IPAB. Furthermore, if the author is a member of a copyright society such as IPRS, the society may distribute the royalties. As to the calculation of royalty amount or license fee amount, all over the world, owners of copyright, charge license fee as a percentage ofnet advertising revenues. The Supreme Court in the case of Entertainment Network India Ltd. v. Super Cassettes Ltd. 2008 (13) SCC 30 at Para 140 had rejected this idea on the grounds that the Indian market is different from those of international jurisdictions. While computing royalty in the case of radio broadcasting, the government has taken a revenue share model instead of a fixed amount model.

Another model is of Needle Per Hour, for instance, if the sound recording is being broadcasted during lean hours in a city with less population, less royalty will be paid. This was the suggested model of computing royalty for Radio Broadcasting by IPAB in the case of Music Broadcast Ltd. v. Tips Industries Ltd. &Ors, dated 30th December 2020. The IPAB calculates the royalty only when it relates to a statutory license as given under Section 31C or Section 31D of the Act, 1947. In the case of voluntary licensing, as enshrined under Section 30 of The Act, 1947 the parties can decide on a royalty model or fee on their own.

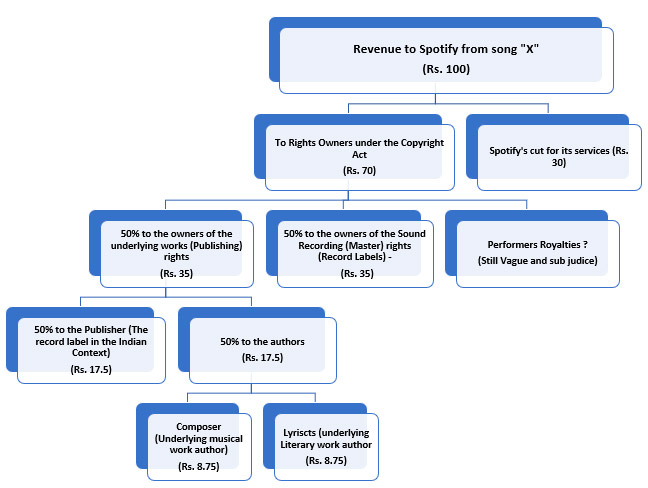

Lastly, sharing the sound recording with online platforms such as Spotify, Apple Music etc the royalty structure varies. The table below shows the royalty structure of Spotify: [3]

References

[1] Section 31D of the Copyright Act, 1947

[2] Music modernization act

[3] See: “Who Gets Paid for the Music You Listen to?: Revamping Music and Copyright in India (Part I)”, SpicyIP, 2020, Available at: <https://spicyip.com/2020/12/who-gets-paid-for-music-revamp-music-copyright-india-part1.html>